Reading Matthew

Each book of the Bible is iterative, building on the pattern of its predecessors. Joshua’s conquests are repeatedly compared to Moses’s. So too, in the Greek texts which make up the New Testament. The ‘good news’ that defines the gospels is that Jesus fulfils the prophesies of Hebrew Scripture. This iterative aspect of Christ’s role is most evident in Matthew’s gospel, whose Christ not only quotes frequently from the Hebrew scriptures, but makes the whole of his life and death one extended quotation.

Of all the evangelists, Matthew has the clearest sense of an audience, writing for Jewish readers. This is evident from the repeated references to the fulfilment of Hebrew prophesies, and from his refutation of the claim that the disciples stole Jesus’s body, a myth which ‘has been spread about among the Jews, to this day’. Matthew’s historically particular address to the as-yet unconverted Jews of his generation gives his account, paradoxically, a general relevance beyond its time. One of the gospel’s repeated refrains (more on the others later) is a denunciation of the evils of the current generation, ‘ye generation of vipers’ as the Authorized Version has it. This moral critique is addressed especially to the hypocritical legalism of the Pharisees and the sophistry of the Sadducees. That this ‘generation’ has a wider significance, extending to us in the present, is suggested at the conclusion of Christ’s fiery prediction of the apocalypse, where he says: ‘Truly I tell you that this generation will not pass before all these things are done.’ Though his words can be taken to refer to the fall of Jerusalem, their spiritual import has not come to pass, so that this ‘generation of vipers’ can only be one to which we also belong.

Nine tenths of Mark’s Gospel is found also in Matthew, and some of what is only implied in Mark is made more manifest. In Matthew, Jesus’s wish to pray alone seems more directly to be a response to the execution of John the Baptist, bringing out more clearly the kind of interiority recognised by Eric Auerbach as distinctive to literature from the Hebrew scriptures onwards. It also (as I wrote last week) makes Jesus’s willingness to heal the people and feed the five thousand something of a personal sacrifice. Jesus presumably wishes to be alone with his grief, not only at the death of a friend and ally, but also at the premonition of his own death. When the people leave, he does go up to a mountain to pray alone through the night, and perhaps there is an element of pathetic fallacy to the storm which ensues, catching the disciples helpless in their boat, until Jesus again breaks his solitude in response to human need, and walks across the waters to calm the storm.

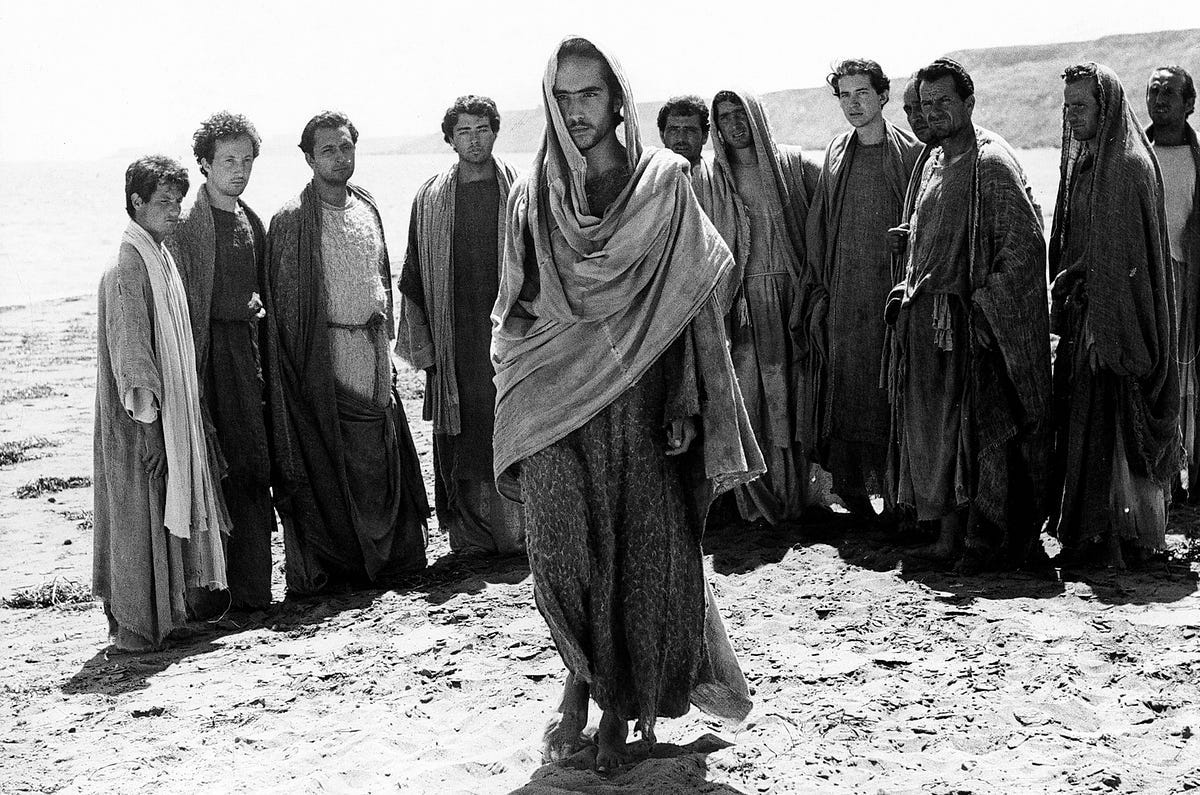

A few details in Mark do not occur in Matthew. Aside from the naked man in Gethsemane, who may or may not be Mark’s self-portrait, Matthew notably does not include Jesus’s reproach to the woman with the haemorrhage for touching him. For the most part, though, Matthew’s Christ is a still sterner figure than Mark’s. Whereas in Mark the disciples cannot cast out a demon because of its power, in Matthew it is because they themselves lack sufficient faith. Matthew’s sternness was part of his appeal to Pasolini. Though an atheist and a Marxist, Pasolini was touched by reading the gospels. He directed The Gospel According to St Matthew in part as a reprimand against the evils of his own ‘generation of vipers’, who were transforming Italy into a commercialised nowhere.

Jesus’s judgement on the perpetrators of these evils is unsparing. Along with reprimanding the sinfulness of his generation, another of Jesus’s constant refrains in Matthew is that there will be ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’, which often concludes the parables. The phrase is another quotation, found in several psalms, as well as Job and Lamentations. The usual sense in Hebrew scripture is that the unrighteous gnash their teeth, in a violent gnawing of the righteous, in unjust persecutions. Jesus inverts this usual meaning. When he mentions weeping and gnashing of teeth, it refers to the sorrows of the unrighteous, presumably in hell. Jesus’s quotation internalises their persecution, implying that for sinners the suffering they inflict on others will ultimately gnaw away at themselves.

This encapsulates one of the enduring paradoxes of a gospel which seems full of paradox and inversion. Jesus tells Peter that he is ‘blessed’ for recognising his true identity, only moments before reprimanding his disciple for trying to say that he need not suffer and die. Jesus’s words to Peter are almost unbelievably harsh: ‘Get behind me, Satan’. There is a hint here of Christ’s humanity. Perhaps he feels the anger we might all feel when offered chocolate during a diet, or when a parent told us to give up because something is too difficult: the feeling of betrayal when we realise that someone’s love for us is too comfortable, unwilling to support us through the pain of becoming better, a love not for our own good, but for a worse version of ourselves.

Christ’s love is never like this: it is a harsh, refining flame. It has paradoxical effects. The first will be made last and the last first, and yet to those who have much, more will be given. The reconciliation of the two apparently contrary statements is simple enough. Those who do not exalt themselves will be rewarded, but something of their reward will be evident during their earthly life, in a more secure happiness. The great inversion which will find its fulfilment at the end of time has already begun.

The last words of Mark’s gospel, in its earliest version, are ‘they said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid’. Matthew ends on a more confident note, with the risen Jesus commissioning his disciples to preach to the whole world (not only ‘the lost sheep of the house of Israel’, as he commissioned them earlier in his ministry). He promises his eternal presence. The gospel’s last words are ‘behold, I am with you, all the days until the end of the world.’ The last word on the disciples listening, however, is more ambivalent: ‘when they saw him, they worshipped him; but some doubted’. We hear Christ’s reassurance through the ears of disciples who at that moment were still coming to terms with what Christ’s words meant, some of whom still doubted the reality of what they were seeing and hearing. Reassurance is right next to doubt, just as blessing is right next to the harsh reprobation of ‘get behind me, Satan’. Faith in the gospel is hard-won, consisting not of easy answers, but a willingness to confront paradoxes and difficulties which might seem impossible.

Only two chapters towards the end of Matthew’s spare narrative produce two and half hours of Bach’s Matthew Passion, where arias and chorales are interpolated with the words of the gospel to embellish the interiority of the narrative’s main characters. Bach’s Passion is astonishing, but the music, the drama, the beauty, is there already in Matthew’s account. One of his many small but significant additions to Mark’s account is of pipers in Jairus’ house, so that Jesus raising his daughter from the dead is preceding by an interruption, suddenly bringing silence to a house noisy with crowds, gathered in mourning.

Matthew’s gospel contains much that is musical, but also has its silences, its moments of difficulty. It is, admittedly, sometimes hard to parse exactly, but the gospel’s ambiguities only serve its message about the vital difficulty of faith. And sometimes the difficulties have their own music. In a moment of particular exasperation with his generation of vipers, Jesus uses an especially ambiguous comparison:

To what shall I liken this generation? It is like children sitting in the public places who call out to others and say: We played the flute, but you did not dance; we lamented and you did not beat yourselves.

Jesus describes children complaining that others have not joined their games. These children could be the viperous generation who demand that Jesus and John the Baptist should fulfil their expectations of what prophets should look like, perhaps specifically suggesting that John lamented too much and Jesus not enough. Or the children could be Jesus and John themselves, calling on a generation who are deaf to their moral injunctions. The contradictory interpretations arise in a passage of contradiction, about a people being called to dance and to lament in almost the same moment. This image of children calling for others to imitate them in their joy and in their suffering is an appropriate one for a narrative which is itself based on imitation and quotation, and one which so often champions the child’s view, with Jesus telling his listeners to ‘become as children are’. It is appropriate also to a gospel which ends with a death that brings an end to death, and a doubt which begins an age of faith.

wonderful <3